[i] Je had een object gekozen? En zou je willen vertellen waarom je voor dit object hebt gekozen?

[r] Die heb ik gekozen als ik terugkijk, wat heb ik gedaan in mijn leven. Die geeft mij een antwoord.

[i] Een antwoord?

[r] In Nederland, ja.

[i] Een antwoord op wat?

[r] Antwoord wat, wat heb ik allemaal bereikt eigenlijk, in mijn leven, vooral in Nederland. Van carrière, of van gezin of zeg maar, werk, dan heb ik echt weinig, om daar de antwoord te krijgen, maar dit is een erkenning. Wat heb ik zelf niet, niet zoveel weet of niet verwacht, dingen die ik gewoon, omdat het moet gedaan worden. Maar, maar er is iemand die ziet dat werk is belangrijk was. En heeft bijdrage voor de samenleving. Dan denk ik bij mezelf, oké, heb ik dus wel bereikt.

[i] Want, kun je vertellen, het is een prijs? En waarvoor en hoe heet de prijs?

[r] De prijs heet Kartini-prijs, het is jaarlijks iemand emancipatie prijs van Den Haag. Tijdens internationale vrouwendag wordt het uitgereikt. Maar is niet zo maar uitgereikt, daarvoor worden 3 door de jury wordt. geselecteerd, voor de laag mensen, het kan ook een product, het ook een persoon, het kan ook een bedrijf, het kan ook een stichting. In mijn geval was ik voorgedragen. als persoon [naam], wat heeft in Den Haag te maken met emancipatie van vrouwen en mannen heeft een bijdrage, dus is emancipatieprijs van de stad uit Den Haag bijdrage van. gelijk, gelijkwaardigheid van vrouwen en mannen. In mijn tijd waren 32 voorgedragen. Daar, daarna 3. gekozen. Er was ook een publiek prijs via internet ook, mensen moeten stemmen, maar de jury wordt ook betaald die prijs, dus toeval ik heb allebei gewonnen. De publieksprijs ook, de Kartini-prijs. Onder andere, waarom heb ik dat gekregen is, staat in de juryrapport dat ik heb taboe onderwerp bespreekbaar gemaakt, binnen Afrikaanse Ethiopische gemeenschap, zoals meisjesbesnijdenis, huiselijk geweld. Om ook rolmodel te zijn, ook in Nederland maatschappij gewoon te participeren. Ik organiseer interculturele activiteiten onder andere vanuit Ethiopische cultuur naar Nederland, laat ik laat ik zien voor Nederlanders en ook andersom. van de Ethiopische of Afrikaanse over Nederland cultuur, dus het is intercultureel activiteit onder andere. Maar is ook een rolmodel van Nederland vluchtelingen vrouwen in Den Haag.

[i] Kun je jezelf voorstellen?

[r] Mijn naam is [naam]. Ik ben 46 jaar. Ja, ik woon in Leidschendam. Ik ben 20 jaar in Nederland. 1994 ben ik uit Ethiopia naar Nederland gekomen als vluchtelinge. Nu woon ik in Leidschendam, daarvoor het was in Den Haag, en op dit moment ik werk in Utrecht, dat is.

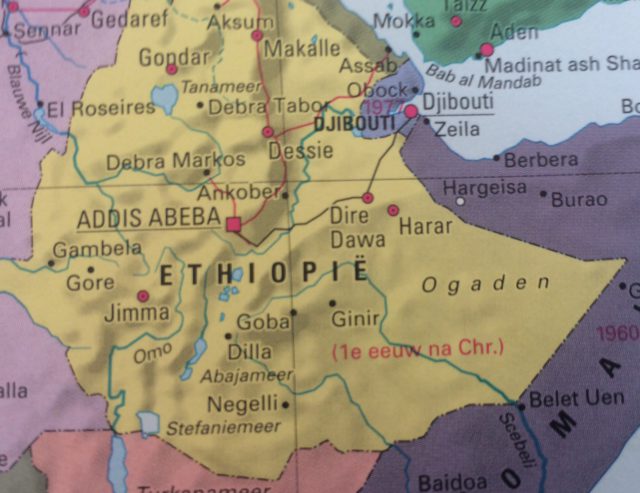

[i] Hé en in Ethiopië, kun je, kun je iets vertellen over Ethiopië, waar jij woonde en ook over je familie?

[r] Ja, ik ben geboren in Noord-West Ethiopië. Met een familie van vijf. Twee meisjes en drie broertjes en ik heb normaal jeugd gehad. Ik had middel, basisschool, daarna middelbare school in de stad. En dan ook in hoofdstad heb ik universiteit gestudeerd, bibliothecaris, toen in mijn tijd was eigenlijk een 2 jaar, daarna diploma en dan heb ik gewerkt.

[i] Heb je in Ethiopië gewerkt in de bibliotheek?

[r] Klopt. Ik heb in de bibliotheek gewerkt en de bibliothecaris beroep heeft zoveel verschillen van bibliotheek. Openbare Bibliotheek of Ministerie of Universiteit, ik heb in speciale bibliotheek gewerkt, speciale bibliotheek is bepaalde vak voor ingenieurs, meer technische boeken, ja, dan was ik bibliothecaris. Toen ja ik wil niet verder in field van bibliothecaris gaan, want ik wil graag meer mensen werken. Toen op dat moment begin ook bibliothecaris is meer. ja computer, computerised en daarom was wel een opleiding in ja bibliothecaris gewoon een ander, andere stapjes te gaan, informatiedienst, maar dat heb ik niet gekozen. Ik was die tijd aan sociologie aan het studeren. Want ik houd van mensen, cultuur en daardoor denk ik ga meer met mensen werken. In tussen ben ik naar Nederland gekomen, ik heb niet afgestudeerd van sociologie. En ja, blijkt nu ik ben heel anders terecht gekomen qua carrière, dat is heel jammer eigenlijk, dat heb ik niet veel does met mijn sociologie opleiding. Ja, dat was de tijd niet, ik bedoel ik was in asielzoekerscentrum. Ik moest 6 jaar wachten en ik word 32 en ik kon dus niet studiefinancieel vragen, ik kon niet verder niet studeren. En op dat moment ik weet het niet ook, ik wist niet ook UAF wat. Ik was in Zeeland, heel echt in het dorp.

[i] Want jij komt uit Addis Ababa?

[r] Ja, oorspronkelijk ik, mijn ouders, ik ben geboren in Noordwest, maar ik heb in Addis Abeba ook gewoond, gewerkt, ja.

[i] En voordat je in Nederland komt, woon je in Addis Abeba?

[r] Ja.

[i] En dan kom je naar Nederland toe?

[r] Ja, dan kom ik naar Nederland ja.

[i] En rond welk jaar is dat ongeveer?

[r] Dat was 1994. dat is in december. Het was 24, ik zal het nooit vergeten het was kerst eigenlijk in Nederland, dus ik moet drie dagen in aanmeldingscentrum om wachten, omdat er waren ja kerstdagen.

[i] Hé, en je komt in Nederland aan en waar in Nederland?

[r] Eerst was ik in opvang OC heet, opvang tijdelijk in Gilze en Rijen. Dat is in Brabant en daar heb ik drie maanden gebleven, ja na drie maanden zoals iedereen moest naar asiel, AZC heette, dat is langer, langer verblijf wachten. bleken, ik was naar Goes, Zeeland verhuisd en toen ook, ja Goes was dicht en ben ik nog in Burgh-Haamstede, dat is ook in Zeeland, is een kleine dorp. Daar heb ik voor de laatste termijn asielzoekers procedure gewacht.

[i] En hoe was je, hoe waren de eerste indrukken in Nederland voor jou, weet je nog wat er, wat heb je toen ervaren?

[r] Klopt. Een of de dingen, is dat was voor mij was dat een shock, ja, ik, het was in december, ik heb niet de juiste kleding sowieso, maar toch als ik heb bomen gezien buiten zonder bladeren, terwijl is nat en vriest. In Ethiopië, het is, je kan alleen bomen zonder blad als droog is, dat was dat was, een controversial [controversieel] voor mij, nog dag en de nacht is ook, het gaat vroeg donker. Het wordt niet zonnig in de ochtend, dat is voor mij een grote verwarring, shock. Echt de koud. Maar ook de positief indruk hoe de straten waren zo netjes en zoveel auto’s, maar je ziet wel alsof, weet je, gewoon zo zo lopen, zo, zo gewoon, dat was mijn eerste indruk, was in Nederland.

[i] En hoe voelde je je toen?

[r] Toen ik kwam? Toen ik kwam, ja, zeker, heel verwarring. Het, het is gewoon heel anders en het was ook een soort militaire kamp. Waar waar was ik in asielzoekerscentrum, je moest 1 keer per dag moet jij stempel halen, handtekening zetten, dan moest je ook 10 minuten lopen, het is ook buiten de stad, als jij naar de stad gaat moet jij. ja half uur lopen of heel openbaar vervoer of taxi, alleen een taxi. En ook, de ene ding, ik wil werken, gewoon dat is de ene ding, heb ik een kamer. Steeds dat ik herinner, een soort kelder, het was ’s avonds, daar in de busje meegebracht, alleen dichtbij het einde aan boord. En ja, een gegeven. Ik wist het niet, weet je en toen ik kwam ’s avonds, er is niemand. Ik moest gewoon in een kamer, gewoon slapen. In de ochtend, ik weet het niet, hoe laat is het? Allemaal is in de war, toen ben ik buiten gaan, buiten kijken, het is donker, dus ik weet niet hoe laat is het eigenlijk. Daarna, ik heb mensen op straat gezien. Dus en een Franse speaker vrouw zegt, manger, manger [eten, eten] dat is de ene ding wat ik van haar begrijp. Toen ik heb samen met haar. Wij moesten in hele rijen om ontbijt te krijgen. Is bijna duizend mensen in dat asielzoekerscentrum. Op dat moment was heel veel [onduidelijk], Somalia van de oorlog, dat is de grote, dat ik moest aan de rijen te zitten. Dat of brood te halen, dat vind ik vreselijk, dat heb ik nooit meegemaakt. En daarna ook ik moet ergens beginnen, dus er moet iemand mij begeleiden, maar er was niemand, toevallig mensen. een man uit Sudan gaf mij rondleiding, waar moet, waar kan ik weet je, kleding wassen of zo, dat was fijn eigenlijk. En dan begin ik gewoon daar te leven en gelijk heb ik gevraagd als ik kan ergens werken. Dat was mijn eerste vraag. Liever in de bibliotheek. Ik mis ontzettend werken. Maar toevallig waren er grote magazijn, alle boeken, Amnesty Internationaal heeft gegeven, maar het was gewoon zonder, zonder iets op de grond. Dan heb ik een beetje, ten minste, Duitse of Nederlands, gewoon, heb ik het wel in een rijtje gezet. Dus dat was fijn voor mij dagbesteding.

[i] Hoe lang heb je dat daar gezeten?

[r] Dat heb ik gedaan 3 maanden. Na 3 maanden ben ik naar een asielzoekerscentrum, daar heb ik, daar heb ik een, een jaar, een een jaar. Toen ben ik terug gewezen naar asielzoekerscentrum Burgh-Haamstede. Dan heb ik een huisje gezocht, dan ben ik in Den Haag terecht gekomen. Dat is het eigenlijk.

[i] Dat is een lang verhaal, hè?

[r] Een lang verhaal is ook heel pijnlijk, maar kan ik niet nu, is het verhaal.

[i] Het is gebeurd.

[r] Ja

[i] En toen kwam je in en hoe begin je dan met Nederlands te leren?

[r] Nederland leren, toen ik was in asielzoekerscentrum, heb ik verteld. Engels gesproken. Ik heb nooit een vertaler gebruikt, gelukkig, ik spreek Engels met dokters of zo, dat is ook fijn, maar ja, begin kom jij wel in, in huis terecht, dan moet jij echt Nederlands spreken. Ik ken paar woorden in asielzoekerscentrum, al, toen ik kwam in Den Haag, ik moest inburgeringen. Ja, dan heb ik test gedaan, op school Mondriaan heet, maar daar daar toets gedaan. Niet voor Nederlandse taal, ze ze had toets gedaan voor intelligentie of zo, IQ, toen hebben zij mij verteld nu niveau 2, mensen die al een jaar eerder in Nederland, maar dat was ook echt. echt, ja als ik terug kijk, dat een of mijn probleem steeds heeft te maken met mijn taalachterstand. Want, ik heb de basis dingen niet weet. A, B, C, D in Nederland, hoe zinconstruction is. Ik heb dat niet in de goede manier beginnen. Toen was niveau 2 mensen dan die had al zien. Ik, ik, ik weet het niet hoe moet dat, ik moet ergens Nederlands spreken, of Nederlands schrijven. Steeds heeft invloed, om af te leren is zo moeilijk, want op dat moment ik heb het kwijt. Het was niet mijn niveau. Dat was de grote mis steeds invloed in mijn taal.

[i] En hoe is dat nu voor jou?

[r] Nu steeds ook, nu steeds voor mijn gevoel, ik kan niet goed Nederlands spreken, de grammatica. De construction, ik ben gewend om in Engels te spreken en dan soms ik gebruik zoals in Engels de grammatica. Maar gelukkig stuk bij stuk gaat beter, maar het is niet zoals ik wil het mijzelf beschrijven of dingen beschrijven. Maar toch wel, ik zou, ik ben nooit, ik durf wel om iets mee doen of zo. Ik zie het niet als als grote belemmering of handicap. Omdat ik heb een andere kwaliteit, ik durf wel en ik ga meedoen. Dus mensen soms zei, ja ze is echt wel, het is niet merkbaar, ja.

[i] En je bent dan in in Den Haag gekomen en heb je ook een verblijfsvergunning?

[r] Ja.

[i] Gekregen

[r] Klopt. Toen, toen ik was in Den Haag ik heb al in asielzoekerscentrum verblijfsvergunningen. Ik moet beginnen. Toen ik heb dat inburgeringen, 600 uur Nederlandse taal geleerd. En daarna was mijn plan, mijn dromen ook, gewoon, gewoon naar school te gaan, mijn sociologie bachelor afmaken. Maar toen ik heb gehoord, nee bij uitkering, je kan verder niet studeren. Het was een grote teleurstelling voor mij en ook werk te vinden in, ergens in bibliothecaris. is ook, ik heb geen ervaring in Nederland, toen begin ik gewoon van de lager niveau te beginnen, gewoon vrijwilligerswerk te doen in de bibliotheek. Ik heb in Den Haag eerste keer bij Vrijwilligerscentrale geweest. Ik heb een vacature gezien: documentalist. Toen ben ik daar heengegaan. Ik weet niet waar, nee nee nee nee mevrouw, u spreekt geen Nederland, dus u kunt dit niet. Maar ik ben mij zelf, het was Prins Claus Fonds. Ik ben zelf daar gegaan, ik zeg ik spreek Engels, ik wil iets dit werk doen. Dat is toevallig, het was een Engels afdeling documentatie. Dus ik heb 3 maanden daar documentatie gedaan en toen is op en toen was een bepaalde tijd schreef, toen moest je zo doen. Dan ging ook nog vrijwilligerswerk te zoeken. Toen heb ik in Gouda, een keer per week, dat is ook Engelse sprekend beetje bedrijf. Een keer per week in de bibliotheek gewoon ook documentatie werk te doen. Als puur dus echt, ja echte, meer Engelse materiaal. Toen blijkt, de, de ene die samen met mij werkt, gewerkt, die zegt, waarom ga je niet. Ze zegt oké, het is heel jammer, jij spreekt heel goed Nederlands nu en dan nog ook, het is nu alles is computerles, het zou mooi zijn als jij opleiding doen. In deze richting. Toen ik zeg ja, daar heb ik geen kans. ik mag niet voor de sociale dienst, zelfs niet vrijwilligerswerk, ik doe het gewoon stiekem. Ik moet werk zoeken gewoon betaalde baan, maar een keer per week ga ik daar. In tussen ik solliciteerde gewoon hard om alle werk te vinden. Zij zegt, tegen voor mij zegt, kijk maar, hij zoeken een school waar kan ik opleiding doen. En ja kan bij ons minimaal 3 dagen werken, als je wil een soort stageplek, wij betalen jou niet. Maar je kan bij ons werken. Toen moet hele grote geluk, ik heb niet zo, oké, toen ik moet toestemming vragen van de sociale dienst, dat mag dat studeren buiten uitkering, toen ben ik terug naar Den Haag, ja ik had er nog een plek. Vrijwilligerswerk een keer per week, maar nu zij wil graag meer 3 dagen per week doen en opleiding kosten betalen. Ik heb overal gezoekt, ik heb in Den Haag , heet Go, anderhalf jaar een opleiding voor bibliothecaris informatiedienstverlener. dat kost 3500,-. Die mensen Gouda, die willen dat betalen ook en ze willen ook stageplek geven. Toen ben ik terug gekomen naar sociale dienst, ik heb dit nieuws verteld, nee mevrouw dat mag niet. Ja, ten eerste jij werkt in Gouda, Gouda is niet gemeente Den Haag. Dat dat kan niet.

[i] Hoe ga jij met teleurstelling om [naam]?

[r] Ja, op dat moment, je, ik ik ben teleurgesteld, maar ik ben iemand daar, daar blijft niet hangen. Dus ga ik ander optie zoeken, ik, ik weet het niet, dan toen, ik zeg, wat dan? Zij zegt, ja, stel als jij in Den Haag werkt misschien, ga kijken. Toen ben ik 100 bibliotheken gezoekt, overal, kleine, grote, heb ik een sollicitatie gedaan om een stage. En toen heb ik het bij Ministerie of Buitenlandse Zaken in Den Haag, zij willen mij hebben, omdat ik spreek Engels en ik heb bibliothecaris ervaring. Prima, ben ik terug naar de sociale dienst, nou, ik heb nu in Den Haag, dus ze kunnen niks zeggen en zij betalen ook voor de opleiding niks. En in toekomst heb ik baan alvast, ik bedoel na anderhalf jaar. Ja dat is gelukkig na echt heel veel, is niet zo makkelijk maar, het is het is wel gelukt. Toen heb ik het. De opleidingformulier alles invult. Ik heb steeds bij mij thuis, dat was ik heb, in september kon niet, door de procedure, in februari wel, kan ik wel op school te zitten. Maar, ik krijg last van mijn ogen. Mijn ogen wordt moe, vooral als ze achter de computer, ik moest echt snel computer leren op dat moment, want de opleiding is in computer. in Ethiopië heb ik niet computer achtergrond. Bibliothecaris was op dat moment, in mijn tijd was gewoon manueel, met hand. Toen ik moet dit. Maar ik kijk wel iets een beetje raar in de computer. Dat is mijn ogen een beetje snel wordt moe. Toen ben ik naar huisarts gegaan, snel om te kijken als ik dat bril helpt. Ja huisarts stuurt naar mijn ziekenhuis en word ik onderzoek gegaan. Je wordt opereerd, ik zeg, maar in, hoe is dat, omdat in februari ik ga school beginnen, ik wil graag snel. Maar ik heb toen gevraagd hoe ziet de operatie? De operatie niet aan jouw ogen, het is jouw oogspieren. Want jouw ogen moe wordt, want jouw spieren is een beetje lui. Dus als jij kind was misschien zou met oefening, maar je bent nu niet kind meer, misschien met operatie kan wij corrigeren. En zij heb zo simpel verteld, in december, 17 december 2002 ben ik naar ziekenhuis gegaan. Zelfs ik heb gehoord gelijk na de operatie zou ik naar terug huis. Tuurlijk ik heb niemand in familie, ik ben ook alleen gegaan. Want zij hebben jou ogen die worden gedicht, ik dacht wordt hier ergens of zo. Ja ik heb de operatie gedaan, toen ben ik van ziekenhuis uit, ik kon niet zien, ik dacht, ik dacht: misschien door de bloed of zo. Nee, en toen heb ik taxi meegenomen, mijn huis was echt 5 minuten, 10 minuten lopen. Ben ik thuis gegaan, dag in dag, dag in dag, ik kan niet zien. Dus ik thuis, ik kan mijn spullen ook niet zien. Ik kan niet meer buiten, ik zie alles zo. Alle, ik kan niet, alleen ik kan zo zitten, dat is de ene ding kan ik zien, maar niet.. Dus, ik, ik moest na een maand voor controle komen, ik moet wachten, in tussen ben ik bij mijn huisarts geweest eigenlijk, omdat ik kan niet zien. Toen na een maand ben ik daar gezegd, ja de operatie, ehm, wat woord hij zei, de operatie was goed. Het is niet mis ge.., het is niet fout gegaan, is mis gegaan. Dus, ja, dan moest ik in de wachtlijst om voor hersteloperatie. Ik heb alleen maar geen zin, of om geen vertrouwen, om dezelfde dokter arts te opereren. Ik heb second opinion gevraagd, ben ik naar Rotterdam geweest, Erasmus. Ik heb 2003 geopereerd, 4 [2004] opereerd om die fout alles te herstellen. Twee keer, zo zwaar tijd, op dat moment ik spreek de taal ook niet goed, ik ken niet zoveel organisaties. Na de operatie ik moest gewoon mijn taxi mijzelf betalen, ik blijf, ik bestel eten van buiten, ik kan niet koken, ik kan niet boodschappen doen. Mijn opleiding is niet meer te doen, zo verdrietig, zo teleurstelling. Ja eindelijk ook 200.., tot 2014 is ook, het is niet echt, dit is niet goed. Dan moest ik nog third opinion vragen. Ik heb gehoord in Leiden is goede dokter. Toen de laatste operatie had ik in 2007 gedaan. Ik, ik blijf met beperking, maar is verbeterd. Al die dubbele zien en wazig. Maar mijn ogen echt wordt heel gevoelig van al die operatie, maar ook de coördinatie aan mijn ogen is steeds heel heel moeilijk, want zit vast. Mijn ogen bewegen niet zoveel, ik moet bewegen met mijn lichaam. Dat geeft zoveel pijn, lichamelijk pijn. En verder ja, daarna heb ik wel de sociale dienst misschien ander opleiding te doen, dat mocht niet. Ik ben toen heel eigenwijs geweest, ik heb zelf opleiding in voor sociale dienstverlening, heb ik bij Holland, InHolland, daar ben ik, toen ben ik 3 maanden daar gezeten. Ik mag niet voor de sociale dienst, dus ik moet af, uit, van school. Ja helaas, daarna zoeken allerlei mogelijkheden. mijzelf te ontwikkelen, dan heb ik zoveel, ja vanaf 2007 na de laatste operatie, 2008 eigenlijk. Ik heb de eerste betaalde baan, bij GGD Den Haag.

[i] Hoe was dat?

[r] Dat is de ene gelukkigste moment dat in Nederland, omdat dat mijn ogen steeds gevoelig, ik word verplaatst bij kringloopwinkel en in de, hoe is dat? In leiden. industrieterrein, ik herinner dat ik 5 uur opstaan, moet ik 7 uur daar zijn. Mijn ogen kan nu niet goed zien in de kledingmagazijn, dat is de werk dat ze mij hebben gevonden.

[i] Wat voor werk?

[r] In H&M kleding magazijn, moet sorteren kleding. Alfabet op de juiste plek. Maar toen mijn ogen was ontstoken, ik kan nu niet zien door de stof. Toen de sociale dienst zei, het is jouw laatste kans, je kan, je krijgt niet meer uitkering, dus ik was zonder uitkering. gezeten voor paar, paar keer. En maar als uiteindelijk ik moet betaalde baan vinden ergens van die situatie en al. Mijn ogen was nog steeds was niet goed. Maar ik heb de eerste baan, betaalde baan bij GGD Den Haag. De reden was ook, ik heb vrijwilligerswerk gedaan voor GGD Den Haag en ik heb informatie over meisjesbesnijdenis voorlichting, daardoor heb ik wel een contract. Maar ik was aangenomen voor tijdelijk project intercultural projectmedewerker, voor Afrikaans, ik geef advies voor de medewerkers, hoe zij kan bereiken Afrikaans, ook hoe zij omgaan met Afrika. Dus die was 1 jaar project.

[i] Vond je dat leuk om te doen dat werk?

[r] Ja, ten eerste dat is echte betaalde baan, de vrijheid, ik hoef niet dwingen, de werk die wil ik niet doen. Dat maakt mijn gezondheid. Ja dat is goed en ten tweede ook de eerste keer contact met Nederlanders, weet je, collega’s, gewoon de cultuur van Nederland samen te werken, dat is ook goeie ervaring geweest. En de derde is ook, tuurlijk, het zit ook [onverstaanbaar] weer, betaalde baan. Dat heb ik opbouwd. Als voor geld, is niet zoveel verschil, is drie euro meer dan uitkering, maar de vrijheid en de beroep en de contact met mijn collega’s. Ja, fijn.

[i] Wat vind jij het allerbelangrijkste? Nu op dit moment, of op dat moment.

[r] Steeds ook, ik vind het belangrijkste om zelfstandig te zijn. Dat is de belangrijkste in mijn leven.

[i] Wat betekent dat voor jou?

[r] Kijk, ik, ik ben nooit afhankelijk geweest, dus je, je komt terecht in jouw leven dat je bent afhankelijk. Dat is gewoon echt moeilijk. te accepteren. maakt niet uit, accepteren ook, maar je hebt ook een plicht, je moet doen wat je wil niet of je kan niet. Omdat jij krijgt uitkering. Je voelt machteloos, jouw zelfwaardering is moeilijk, je voelt schuldig dat je kan jezelf niet. Ja niet, je hebt wel opleiding gedaan, alles achter je laten en kom jij in andere situatie, een ander land, vooral is ook een complicatie met mijn ogen, ze heeft enorm invloed met mijn leven. Ja, en daarvoor heb ik ook. die traumaverwerking. Ik heb in alles stapje, maar toch soms dan kan je niet verder. Je wordt beperkt, dat geeft machteloos, het moment als jij werk, als jij betaalde baan, ten eerste de zelfstandigheid en de ruimte en de vrijheid, ja, dat geeft heel fijn gevoel.

[i] Is vrijheid belangrijk?

[r] Ja, voor mij dat is de belangrijkste, daarom ben ik ook hier. Waarin we iets van meningsverschil, of wat, wat is het, dat vrijheid is de belangrijkste ding en zelfstandig.

[i] Hoe zou je vrijheid voor jouzelf definiëren?

[r] Definiëren. Voor mijzelf vrijheid definiëren dat eh, in, in de kleine, in de kleine, niet als politieks of zo , maar gewoon, gewoon als jij vraagt mij nu op deze moment, dat ik niet afhankelijk van iemand. Iemand niet bepalen mijn leven, dagelijks leven, wat moet ik doen? Wat moet, dat dat, nog, weet je dat begin van mij nog dichterbij, tuurlijk. Er is heel veel als wij praat vrijheid, maar voor mij vrijheid de ruimte krijg wat ik wil doen. De ruimte krijg dat ik niet, niet alles, maar ten minste dat niet iemand anders beïnvloed. Dat, dat is het belangrijkst.

[i] Ik had een vraag, dat, toen ik jouw gegevens ging lezen en dacht ik, wat betekent kracht voor jou? Innerlijke kracht

[r] Innerlijkheid. Voor mij, ja mijn leven heeft zoveel tegenslaan in mijn leven. ik heb een, ik heb geen echte makkelijk leven. Dus, altijd vallen opstaan. Dus ik weet dat, ik heb kracht nodig om nog, nog meer opstaan. Dan dat is de kracht wat denk ik heb ik. Soms ook ik zie het van andere mensen als inspiratie.

[i] Zoals wie, wie is jouw grootste inspiratie?

[r] Uhm. Weet je als ik als ik in mijn land zien, voorbeeld mijn tante was mijn inspiratie, zij is zusje van mijn vader. Het is een echte vrouw, achteraf weet ik, toen ben ik in Nederland bent, ik heb leiderschapscursus gedaan in Amsterdam. Toen zij vroeg mij, wie denk jou, wie denk jij in jouw familiekring die, die jij lijkt? Toen weet je ik moet iemand zoeken die, wie, wie is nou nou in mijn dus inspiratie. Toen heb ik het haar ook interview voor zij gaat dood gelukkig, hoe haar leven was. Zij was dwingend getrouwd, zonder had had zij wil. De man die wil trouwen toen was in Ethiopië, tuurlijk op dat moment. En toen zij is gescheiden, toen zij is gevlucht naar andere stad. Zij is getrouwd een man die echt rijk is en gewoon administrator, gewoon bekend in de, in de omgeving, maar omdat zij zoveel ambitieert. zij wil niet dat soort leven, zij wil zelf iets doen, zelf verdienen. Toen zij is gescheiden en had ze nog een bar/restaurant geopend. In dat tijd hè, bedoel ik, nou, zij is niet meer helaas, dat is misschien 16 jaar geleden. 15 jaar geleden, en al die, weet je, al haar, ook dat moment bedoel ik, toen was op dat moment en de omgeving, waar komt het vandaan. Ook gewoon echt, niet, zij was nooit. ook naar universiteit of school of zoiets geweest. Maar zij zegde oh als ik maar, als ik maar ben ik op school geweest zei ze 1 keer. Zoveel dingen zitten in mijn hoofd maar helaas. Weet je, ik ben niet op school geweest, dus, dat soort dingen wat zij zegt voor mij, dat iemand moet ontwikkelen, je moet doorzetten en zij wil niet afhankelijk van iemand, zij wil niet ook gewoon huisvrouw, zij wil gewoon graag zelf daar dingen doen. Dus dat denk ik dat. In Nederland, oudere mensen vooral, die zijn voor mij inspiratie en hoe zij zich al van hun landen, weet je op straat als ik loop, zij gaat, alles gewoon weet je in de haar in de controle. Ik ja, dat dat weet je dat geef jou, ja ik ook, sowieso, ik hoor hier bij en dit mensen ook, als ik zie die mensen ook, ik krijg ook inspiratie. De ander is ook die buitenlanders vooral, net als ik, gewoon gevlucht hier gekomen. Hoe moeilijk is de leven gewoon een ander land worden, maar toch wel een kracht, weet je, met z’n kinderen opvoeden, andere taal leren. Hoe hoe hoe dat is. Dus ik krijg ook daar ook inspiratie eigenlijk, uit allerlei bronnen.

[i] Je doet veel in de in de wijk en ook met Ethiopische gemeenschap of de Afrikaanse gemeenschap?

[r] We hebben een stichting, ik ben voorzitter en ook oprichter. Toen ik had gezien daar, ik doe heel veel mijzelf, vrijwilligerswerk, later ik had besloten misschien als ik een stichting opricht, misschien zal nog meer kan bereiken. Toen, bepaalde doelen hebben wij de stichting opricht 2008, heet stichting Gobez. Heeft de doelstelling intercultural activiteit organiseren. Ook gezondheidsvoorlichting, vooral taboe onderwerpen bespreekbaar maken.

[i] Wat zijn taboe onderwerpen dan?

[r] Zoals meisjesbesnijdenis, huiselijk geweld. Die zijn meer..

[i] Voor de Ethiopische gemeenschap bedoel je?

[r] Niet alleen voor de Ethiopische eigenlijk, het is voor, voor Nederland vaak. Sowieso dit voorlichting geef ik niet alleen voor de Ethiopische, maar ook voor andere migranten, huiselijk geweld bijvoorbeeld, meisjesbesnijdenis is specifiek Afrikaans. Niet alle Afrikanen, alleen 20, 29 landen die meisjesbesnijdenis voorkomt. Want Ethiopië is onder andere een land van meisjesbesnijdenis die ook voorkomt. Het is, het is, het is zo grappig hoe ben ik ook betrokken in dit meisjesbesnijdenis voorlichting? Ik ben 2007 in conference geweest, ik was uitgenodigd via vluchtelingenwerk. Ik heb helemaal geen idee, in Rotterdam, ben ik daar geweest. En toen was zero-tolerantie, het is 6 februari, het is jaarlijks wordt in Nederland gevierd tegen meisjesbesnijdenis. En daar, ik zie toen ik zat tussen Nederlanders een vrouw en er komt een presentatie over meisjesbesnijdenis, een film. En toen ik heb dat gezien, het was Ethiopische meneer die uit Ethiopia wordt uitgenodigd als presentatie moet geven. Toen ik in Ethiopia was, toen ik weet dat meisje, meisjes was besnijden, maar het was niet en issue dat je hoort en ziet iets, het is gewoon als normaal ding gebeurd. Maar ik heb nooit ook in mijn ogen gezien dit gebeurtenis. Dus toen ik heb een film gezien, ik vind zo vreselijk. Later, nee toen aan op dat moment als Soedanisch, Somalische vrouw bijna aan de tranen, zo traumatised. Ik, ik ook, zo’n, ik zat ook zo te kijken, naast mij Nederlanders vooral, zei, waar kom jij vandaan? Van Ethiopië had ik zegt, oh, jullie zijn de moeilijkste mensen te vinden. Dus, hoezo? Ja vereniging in Den Haag zoekt Ethiopische mensen om training te geven en voorlichting te geven omdat jullie land ook meisjesbesnijdenis en nog de risico landen. We hebben een pilot project. Ik wil het wel doen! Toen zijn we in de pauze naar hem collega, introduceer, en dus ik kende vrijdag, maandag ben ik naar GGD Den Haag, toen ik heb het gehoord dat ik krijg training als [onverstaanbaar] persoon, meisjesbesnijdenis, ja voorlichting geven voor de Ethiopische gemeenschap. Toen ben ik ander collega gezoekt. En wij waren in een hoekje een training en voorlichting voor meisjesbesnijdenis voor de Ethiopische groep te geven. Ja, tot vandaag doe ik vrijwilligerswerk ook. Ik zit soms samen met GGD Den Haag onder andere

[i] En wat voor ander soort vrijwilligerswerk doe je momenteel?

[r] Ik heb zoveel vrijwilligerswerk gedaan. Vooral elke project wordt in Den Haag bijvoorbeeld beginnen, wordt ik gevraagd. Vooral als het participatie is. Nou, ik weet niet, het is toch omdat het is zoveel, ik kan zeggen beter nu wat ik doe. Door de stichting het is vrijwilligerswerk, waar kan zij voorlichtingsbijeenkomst is, we gaan ook bij mensen huis bezoek, nieuwkomers begeleiden. Vaak ook je wordt uitgenodigd bijeenkomst te wonen, dat is puur voor de stichting. Maar dat de meeste is in Den Haag. Ik woon sinds 2008 in Leidschendam. Tuurlijk ik, ik woon hier dan ik heb een gevoel gekregen. dat moet ik hier iets ook bijdragen. Toen begin ik, Leidschendam is een hele kleine dorp, Nederlands dorp. Is heel anders Den Haag, het is niet multicultral. Ik moet eventjes, even wennen, mijn weg te vinden. Toen ben ik in de bibliotheek geweest, ik wil Ethiopische koffie ceremonie doen, dat heb ik in Den Haag ook gedaan. Van koffie tijd voor ontmoeting. Als ik niet in de bibliothecaris werken, ik mis bibliotheek mij vaak. Dan ga ik vaak naar bibliotheek. Maar ik wil iets doen in de bibliotheek, dus dat is mijn echte, mijn eerste, mijn eerste plicht daar wil iets doen. Toen heb ik in Den Haag in de wijkbibliotheek gedaan, nou kom ik in Leidschendam gevraagd. Toeval, toevallig na 1 jaar zij hebben mij uitgenodigd, het was maand van geschiedenis en thema, er wordt presented over Nederlands geschiedenis. Ik mag over Ethiopische geschiedenis presentatie geven. Dus ik heb daar een kleine exposition en koffie ceremonie gedaan. Toen begin in de wijk een beetje te participeren, dat was niet genoeg, later heb ik ook met in de stichting heb ik bijeenkomst organiseren, eten, onder andere koffie ceremonie. Maar dat ook, ik heb een gevoel dat is, dat is, ja dat is ook steeds. ik wil hier ook concentreren, waar ik ga wonen, vaak ben ik in Den Haag. en vorig jaar, een vrouwendag, kwam een meisje bij mijn huis, niet meisje, opbouwmedewerker. Zij zoekt vrouwen over een droom, een droom. Zij verzamelt dromen van vrouwen. Dus die, die meisje die werkt in Leidschendam, die verzamelt dromen die kan andere vrouwen inspireren voor de vrouwendag. Oké, en ik ken haar niet, zij komt bij mij net als jou mij interviewen. En zij vroeg mij over mijn dromen. Dromen die waargemaakt, dromen niet. En misschien ook die dromen waargemaakt of niet. Toen ik heb al de grote dromen verteld, dat zou ik maatschappelijk werkster willen worden, graag vaste betaalde baan hebben onder andere. Maar later ik heb haar gezegd als ik geld heeft, als ik de taal goed spreek. als ik het ruimte heeft, wil graag theater spelen. En toen vroeg mij welk soort theater? Nou en theater, gewoon mensens leven, zelfs inclusief van mijzelf, zijn verschillende thema. Ik zie in deze wijk, [onverstaanbaar], misschien iets mensen in contact brengen. Toen, ja toen zij was een beetje stil en de later na twee maanden, zij had mij uitgenodigd voor gesprek. Waarom zou jij niet nu de theatervoorstelling? Ik zei op dit moment mijn prioriteit werk te zoeken en de taal ook te leren en dat, dat is ook en heb ik geen geld om de theater te leren, weet je zo. Oké, stel als ik jou de kans wil geven nu? Weet je, theater ga je maken, dan kan je zien in dit wijk, iets dat kan wij doen. Ja toen ik heb gezegd, ik heb bepaald idee, bepaalde thema uitgegeven. Eigenlijk graag op een manier mensens leven hun verhaal gewoon te spelen. Het is pijnlijk soms, mensen ook zij zien het niet als ik heb nu mijn verhaal vertel, het kan ook 24 uur, maar het is toch lastig voor de mensen misschien theater. Toen heb ik bij de gemeente gevraagd, het project, zij hebben een project gemaakt. En ja, dat wordt nu theater. Steeds ik speel de theater.

[i] Je speelt in een theatervoorstelling?

[r] Ja, klopt.

[i] En hoe heet de theater

[r] Ongehoord. Ja, Ongehoord. Ongehoord ja bestond als de 9 spelers. ik ben een van de spelers, eigenlijk initiatiefnemer. Het was vorige jaar juni 4 keer in Leidschendam te zien, maar het was uitverkocht. Ze gaan ook nu weer 25, 26, vandaag wordt ook gespeeld. Dus straks, ik speel ook in de. in theater.

[i] Vind je het leuk spelen voor een publiek?

[r] Ja, het is leuk, want de proces was zwaar want het is persoonlijk verhaal. Dat is al herinnering, al de pijn, het is gewoon echt verhaal, echt levensverhaal. het was wel echt zwaar proces geweest, maar nu begin ik aan het genieten. Dus echte leuk en aan de compliment krijgt van andere mensen en nog ook heeft beweging meegebracht. Voorbeeld voor handicap was niet lief. juiste bibliotheek, door de theater is nu lift is ook gemaakt en de gemeente dit heeft gesponsord, gesubsideerd, nog een keer voor ambtenaars te zien. Dus dat wel effect heeft, niet alleen genieten, maar heeft wel beweging. Dus ik ben een of de Leidschendammers, dus.

[i] Ben je bekend hier hier in de buurt? Herkennen mensen jou van de toneel?

[r] Voor de toneel. Nee, sommige mensen kennen mij, maar ik heb eerder met boeken gewerkt. bij Prinsenhof. Nog ook een tijdschrift dit maand ook nog ik word interview. Volgens mij langzaam mensen kunnen mij kennen leren.

[i] Leuk.

[r] Ja.

[i] En voor wat voor publiek vind je het leukst om te spelen? Gewoon mensen van de wijk, of, ja, voor welke mensen spelen jullie vaak?

[r] Klopt. Ja, eigenlijk de publiek is divers. Ik vind het ook leuk dat voor echte divers publiek te gaan, ik heb zelf ook heel veel mensen uitgenodigd. Wil graag nieuwkomers, vluchtelingen, maar ook gewoon blank Nederlanders, hoe zij denken over vluchtelingen of migranten, over handicapte mensen, gewoon beoordeling heeft van iemand. Of mensen in een hoekje laten staan. Maar welk, welk situatie van de mensen zij begrijpen niet, waarom, waarom ben ik blijf zo achter staan. Of maakt niet uit wat [onverstaanbaar] is, dus in Leidschendam is een beetje, dit Prinshof heet de wijk, de meeste buitenlanders wonen. Dus niet zoveel interactie met Nederlanders. Juist de theater was fijn omdat veel Nederlanders er waren in de voorstelling. Dus die had beetje begrip voor de mensenleven hoe is het. Maar is ook voor iedereen vindt het leuk, dat theater laten zien en iedereen vindt het ook, gewoon weetje, gewoon echt, sommigen zijn huilen, sommigen zijn huilen, het is heel emotioneel. Met heel veel mensen wordt emotional door de theater, maar is ook later zei ze [?]

[i] Hoe ga jij daar mee om als jij ziet, je bent aan het spelen en je ziet mensen emotioneel worden, huilen, lachen, wat doet dat met jou tijdens het spelen?

[r] Klopt. Ja, nu ben ik over, over gekomen, hoe hoe heet nou? Ik was zelf ook in de emotion, vaak. Dus ik ben aan het werken mijn eigen, ik zit ook nog in mijn, mijn emotie, maar gelukkig nu is minder. Ik, ik speel gewoon.

[i] Je speelt jezelf?

[r] Ja, ik speel mijzelf en mijn verhaal. Een stuk van wat ik heb jou hier verteld, komt terug naar de theater ook. Ik speel mijn eigen verhaal. Ieder spelers, ook spelen, speelt eigen verhaal, echte verhaal. Want zo komt ook instanties, weet je, die samenwerkorganisaties soms ja, het is verschil. Mij, mij, mijn pad is meer over, over ik. om, over mij, dat is ook of mijn dromen geweest. Dat theatervoorstelling te maken. nou, dat, dit is nu waargemaakt, dat is echt fantastisch. Dat iemand je horen, al die misschien jouw droom, dat is een of mijn succes. een of, een of mijn bijdragen eigenlijk voor Leidschendam.

[i] Hé, en je komt ook, je werkt ook in Utrecht?

[r] Nu op dit moment.

[i] Wat was, wanneer was de eerste keer dat je in Utrecht komt?

[r] Ik was echte toevallig is Utrecht. Utrecht. vanaf 2007 ben ik vaak in Utrecht, die meisjesbesnijdenis voorlichting opleiding, het was in Utrecht. En dan heb ik voorlichter opleiding voor huiselijk geweld, dat was ook in Utrecht. Het heet Pharos, een organisatie voor migranten en vluchtelingen, vluchtelingen. Over gezondheid, kennis en expertisecentrum. Daar vaak zij heb cursus en zij heb opleiding voor voorlichter. Vanaf 2007. ben ik heel avond, maar 2011 heb ik ook baan daar, mijn tweede betaalde baan was in Utrecht, bij GGD Utrecht. Dus, ik heb echt een bijzondere band nu ook met Utrecht.

[i] Wat vind je, wat is je eerste indruk als je in Utrecht bent? Wat valt je op?

[r] Natuurlijk vaak was gewoon even gaan, even terug, maar daarna ben ik meer. weet je, meer meer in de stad. Ja ik vind dit gewoon, de winkel, de de winkelcentrum na Centraal Station, Hoog Catharijne, dat vind ik dus ook een apart.

[i] Waarom?

[r] Daar loop jij zonder. Ja, daar loop je zonder regen of niet net als in Den Haag, gewoon binnen, het is fijn daar binnen te lopen. Als je daar uitloopt, de Oude Gracht, ik weet het niet, ik vind die zo mooi. Ik krijg daar gewoon ander gevoel.

[i] Kan je dat gevoel beschrijven?

[r] Weet je, qua van de drukte dan zit jij beneden. Ik weet het niet, een, een soort, een soort. binding, weetje, gewoon daar als ik daar zit, gewoon.

[i] een binding met.

[r] Een binding gewoon voor mijzelf of bepaald tussen een water en bepaald twee muren, dat je wil, weet je gewoon een soort grens. Dan kan meer bij mijzelf zijn en ook genieten wat, wat hier. Ik houd van water, ik ben, ik kom, ik ben opgroeid naast water, Nijl en die grote meer. Water zo geeft mij meer rust. Maar is het ook, is anders, Nederland is heel vla, plat. weet je dan dan dan krijg je gevoel van ergens een grens. In Afrika is meer bergen en meer ander landschap. Maar in dat beetje iets beneden kan je hoog kijken, weet je, misschien dat! Ik weet niet, het heeft wel fijn gevoel. Rust en is anders, dat dat vind ik, ja daar daar wil graag gaan. En daarnaast ook Ethiopische restaurant, haha, tuurlijk. En ga ik heel af en toe als ik de behoefte heeft in Ethiopisch eten. Het is gewoon echt 2 minuten lopen naar de Oude Gracht.

[i] Ken je veel Ethiopiërs in Utrecht?

[r] Nu door mijn werk eerder. Ik heb het, ik heb gewerkt bij GGD Den Haag voor bepaald onderwerp van de meisjesbesnijdenis, dat is niet voor specifiek voor de Ethiopische, van de hele Afrikaans. Dus op dat moment ik heb de mensen kennen leren. Op dit moment via via. Nu ik ben meer Ethiopische mensen daar kennen leren voor mijn werk.

[i] Is dat prettig voor jou om meer Ethiopiërs te leren, leren kennen? in Utrecht?

[r] Ja, ja zeker. Het is, het is wel leuk en onder andere is ook, ik heb het wel in tussen tijd gezien, voorbeeld in Den Haag zijn Ethiopiërs. ze zijn makkelijk te vinden, want we hebben een stichting, we hebben de netwerk en weet je als ik ze in Utrecht, het is echt moeilijk mensen gauw te vinden. Ik heb geleerd hoe belangrijk die zelforganisatie bijdragen van. zeg maar mensen te participeren hier. Wegen, ergens weg te vinden.

[i] Is dat anders in Utrecht dan in Den Haag?

[r] Ja, ja.

[i] Wat is er dan anders?

[r] In Den Haag als ik Ethiopische mensen wil vinden. Nu kan je mij vragen gelijkertijd ik kan 10 mensen naar jouw telefoonnummer geven.

[i] Ja.

[r] Gewoon waar ik ben van mijn activiteit, zij komen vaak, we hadden de contact. Maar in Utrecht, de, je vraagt 1 persoon. Je kan niet gewoon die telefoonnummer zo krijgen. En die mensen ook, die zijn ook niet gewend denk ik bijeenkomst, gewoon bijeenkomst te wonen, dus.

[i] En en denk je dat dat te maken heeft met de stad zelf, met Utrecht zelf?

[r] Nee. Juist omdat er veel centrale punten daar voor de Ethiopiërs zelf. Ethiopiërs bij elkaar te komen, iets activiteits te doen, ook en en organisatie die mensen bij elkaar verzamelen. Je kan hier niet terecht ergens. die mensen te vinden. Waar kan je mensen, op straat? Dat is toch moeilijk. Ja.

[i] En hoe heb je dat dan gedaan, want je komt in Utrecht voor de cursussen en de voorlichting te geven en de scholing, He? dat is nu de professionele kant.

[r] Ja, ja.

[i] En vanuit die professionele kant, hoe kom je nou met die mensen, met de Ethiopiërs die in Utrecht wonen in aanmerking?

[r] Ja.

[i] Hoe doe je dat?

[r] Bedoel van eerder werk of wat …

[i] Ja, van toen en nu?

[r] Toen, ja. Toen toen toen, toen was 2011. Ik moest van best voor Afrikaans van ander Afrikaanse landen ook moest werken. Het is toch grappig de ander Afrika landen heeft en stichting, of een kerk, waar kan ik echt terecht gaan. Maar voor de Ethiopische waren niks.

[i] En welke andere Afrikaanse landen?

[r] Somalia, Togo. Ghana, Burkina Faso en Guinee, ja, daar zijn wel, en Eritrees en Ethiopische waren de enige die niet een stichting dus, eigenlijk ik heb mensen gezoekt ook op straat. Op de restaurant, of Burger King, bij station staan om mensen ook ontmoeten. Gewoon zo, maar later, ik ben nog naar de kerk geweest en.

[i] Er is een Ethiopische kerk in Utrecht?

[r] Nee, er was een soort festival, kerkdienst gewoon, ik heb het gehoord, er was een keertje fundraising voor de kerk, het was toevallig in Utrecht organiseerd. Toen ben ik daar, heb ik via via met mensen contact daarvoor, toen de GGD heeft gesponsord, de zalenhuur en onder andere ook van de mensen te eten. Dat heeft, de project heeft weer ruimte, geld, dat te doen, omdat zo moeilijk, moeilijk onderwerp. Dan moet jij aanpassen, bij de mensen, bij de cultuur.

[i] En wat was het onderwerp dan?

[r] Meisjesbesnijdenis. Het was een pijnlijk project voor GGD Utrecht. Niet alleen Utrecht, zes steden, maar Utrecht heeft moeilijk dit pijnlijk project te doen, ze hebben weinig ook gedaan, drie jaar hebt zij geld, maar zij zoekt iemand dit te doen, toen was ik heb aangenomen, en voor mij was Utrecht eigenlijk nieuw. Bij de Ethio.., de Ethiopische was de moeilijkste groep bereiken op dat moment voor mij. Want er, het was ergens heen, geen centraal punt daar mensen kan vragen. Maar uiteindelijk het is wel gelukt. Door, door een bijeenkomst, gewoon van hun zelf te sponsoren, tijdens dat bijeenkomst, het was wel landelijk mensen dag, er komen natuurlijk 100 mensen, toen we hebben daar voorlichting gegeven.

[i] Hé, voorlichting dat is dus heel specifiek hè.

[r] Meisjesbesnijdenis, ja.

[i] Specifiek thema, vak.

[r] Klopt.

[i] Hoe, kan je daar iets over vertellen, bijvoorbeeld, ik heb nog nooit voorlichting gegeven over iets, hoe doe je dat voorlichting geven?

[r] Voorlichting is een informatie. er zijn verschillende manieren voorlichting te geven, afhankelijk de thema. Je moet een bepaald, bepaalde normen weten. De groep, hoe de groepsdynamiek is. Wat cultuur past bij de groep, voorbeeld ja, als ik naar Ethiopische kerk ga, ik moet echt aankleden zoals bij mensen. Of als ik moskee ga, dan moet ik ook een soort hoofddoek zo hebben, je moet je aanpassen. Taal is ook belangrijk, je, ik heb een meestal eigen taal voorlichting gegeven voor de Ethiopiërs. Als voor ander Afrikaans of ik moet aanpassen als mensen Engels spreken in Nederland. Maar wat belangrijkste ook kennis over de onderwerp ook.

[i] Maar hoe ga je dan zo’n moeilijk, pijnlijke thema in de gemeenschap brengen, hoe doe je dat?

[r] Ja, je je gebruikt allerlei manieren, modellen, voorbeeld. Als ik mensen zeggen houd van muziek voorbeeld, kan je muziek gebruiken die dag tijdens de voorlichting. Als ik mensen, doet gezelligheid, voorbeeld huiskamerbijeenkomst heeft, wij gebruiken Ethiopische koffie ceremonie. Ik, ik gebruik vaak dat mensen beetje losser en eigen zelf te zijn. Dus je past bij de groep, soms van de cultuur of wat wat maakt het, beetje meer vertrouwig, je je moet het ook kiezen. Wanneer vinden mensen gewoon voor vrij. Bijvoorbeeld ik geef voorlichting af en toe alleen voor vrouw, soms voor de jongeren apart. Jongeren die geboren of opgroeid is heel anders, dan, dan wij, later naar Nederland gekomen. Bij mannen, soms als je het gevoel krijgt, nu is het bespreekbaar, dan ga je gemengd, gemengd, ik bedoel samen, gezamenlijk voorlichting geven. Dus, het is niet alleen kennis, maar je moet ook over echt over de groep. En ook, je moet zo flexibel zijn.

[i] Kan je een voorbeeld geven van flexibel zijn?

[r] Voorbeeld, professionals, zij willen alleen werken vanaf 8 tot 6, voorbeeld hè, een werkdag. Ik ben flexibel op als ik de groep zondag of zaterdag, dan ga ik die voorlichting aanpassen bij hen welke tijden past. Dat is ook een flexibiliteit en de tweede is, ik kijk ook wat zij hebben nog meer nodig. Soms is niet mijn taak, maar soms zij komen met andere problemen. Dan moet je de mensen helpen in geval dat de voorlichting gaat, met soms kinder oppas, moet je regelen, van hen ook, soms ook ja bepaald evenement voorbeeld wij kan gebruiken, voorbeeld Moederdag. Maar geen kleine cadeautje voor Moederdag, dan wij spreken over moederschap. Weet je, je moet creatief zijn en elke moment ja, die mensen hun zin te krijgen dat voorlichting te krijgen of dat bespreekbaar te maken. Dat is de flexibiliteit, het is geen echt standaard, standaard, de ja zoals professionals. Het is niet om van hen, zij moet zo komen, dat werkt niet, die mensen zijn nog niet, die zijn de proces, dus je bent bezig ook, een mis de proces, soms moet je aanpassen, vaak. bij de bij de groep voorbeeld, paar paar mensen die kan wel met powerpointpresentatie omgaan, soms die moeten sheets in eigen taal, ja dat bedoel ik.

[i] Wat vind je het leukst aan dit werk?

[r] Ik ik ik wat ik vind ik leukst is dat, ik vind het zo leuk om te leren, ik vind iets leuk zelf ook nieuw dingen te leren, maar dingen te horen. Bewust te worden, dat wil graag ook overdragen aan de anderen. Kennis overdragen, dat dat vind ik de mooiste.

[i] Ja?

[r] Ja. Ik ik weet niet misschien van mijn oude vak ook, is bibliothecaris, je geeft maar informatie voor mensen of zo . Steeds ik vind dit of boeiend, dat kennis overdragen.

[i] Dat doe je graag? Met bij, bij de Ethiopische gemeenschap, maar ook bij de Afrikaanse.

[r] Bij iedereen!

[i] bij iedereen.

[r] Bij iedereen, voorbeeld bij Nederlanders over Ethiopiër voorbeeld, ze hebben heel weinig informatie over Ethiopiërs, ze hebben alleen maar over oorlog. honger, maar buiten dat is echt fascinerend land, heel veel geschiedenis, cultuur en dat geeft ook workshops, lezing, soms koffie ceremonie organiseren. Maar is ook informatie over, gewoon facts, weet je reisinformatie.

[i] Je hebt ook een eigen bedrijf hè?

[r] Op dit moment ik ben bezig met mijn eigen bedrijf op te zetten, ik ben aan de beginfase aan het oefenen. Daar wil graag onder andere de voorlichting sowieso, voorlichting geven. Ook informatie over Ethiopië, of workshop, of lezing, wil graag dat geven. Daarnaast ook af en toe wordt bepaalde project net als nu BMP heeft veel werk, omdat Ethiopisch bent, Ethiopische achtergrond. Daar ben ik nu bezig met dit en dat komt misschien komt wie weet ander onderzoek, dus ik, ik kijk, maar zoveel mensen ook en tegenwoordig, zij gaat naar Ethiopië om daar, daar te werken, te leven. Maar die zijn ook heel adoption ouders, als die het behoefte heeft dan ga ik wel, ja informatie geven. Ik, ik gebruik het, cultuur is als instrument. Instrument van integratie, de motor van intergratie, voor mij, ik ben in Nederland. Heel veel gebruik, Ethiopische cultuur, ten eerste een middel van mij in contact brengen aan de mensen.

[i] De Ethiopische cultuur?

[r] Ja.

[i] Kun je, ik weet niks over de Ethiopische cultuur, wat gebruik je van de Ethiopische cultuur om die integratie. teweeg te stellen, tot stand te brengen. Kan je daar een voorbeeld van geven.

[r] In mijn manier, bij mij zelf, wat heb ik gedaan toen ik kwam hier in Nederland, gewoon gewoon mensen, gewoon gewoon contact te nemen. je bent nieuw. En het is niet gebruik dat ik toen heen gaat bij iemand, hallo en kom koffie drinken, dat werkt niet. Er moet iets van mijzelf komen naar een contact tussen de mensen komen. En toen begin ik bij mijn buren om te vragen koffie bij mij te drinken. Dus in Ethiopië is gewoon dagelijks normaal vinden om met jouw buren koffie drinken, maar in Nederland is gewoon niet de afspraak. Of zelfs, ja, zelfs is niet. Dus toen begin ik bij buren, soms lukt niet, duurt het misschien jaren, maanden, samen met de buren koffie drinken. Maar daar buiten, ik wil in de wijkcentrum ook Nederlandse mensen in contact komen. En de ene manier op dat moment, ik moet gebruiken wat ik heb, mensen van gevoel, als je heeft, je bent welkom, als ik maar wil wil wil wil, dan veel minder welkom. Dat is gewoon internationale standaard. Dus, als ik heb ik vertellen te laten zien wat van Nederlanden mensen vinden mooi, het is heel open staan van nieuwe dingen te weten of te vragen, ze zijn nieuwsgierig. Toen begin dan vrienden maken. Toen heb ik het contact met mensen daar leer ik van, hè, ook dit is van integratie, je hoeft niet van een kant te komen van mijn gevoel, juist omdat die cultuur die gastvrijheid van die Ethiopische cultuur voorbeeld mensen laten eten, laten koffie drinken, gewoon weet je, het is gewoon zo simpel dingen. Of kleding, nu ook, wat ik heb is Ethiopische kleding eigenlijk, als ik ergens gaan, festival, dan haal ik Ethiopisch. En mensen zij gaan gauw mij spreken, waar kom jij vandaan, wat is, wat is this? Dan ga jij interactie met mensen. Zoiets. En gauw, ook Ethiopische mensen, natuurlijk, iedereen is trots. Wat, wat heeft iets positiefs, die kan ik extra stimulerend zijn naar de ander brengen, dus dat gebruik, het is, het is een, ja een soort instrument eigenlijk. Die, die dingen die, wat heb ik meegenomen uit mijn land, de goeie cultuur dat bewaar ik het, de slechte traditional zoals meisjesbesnijden, dat wil graag dat ook bespreekbaar maken. Ja, dat is het zo.

[i] De contact met mensen is belangrijk hè, voor jou?

[r] Ja ik houd van de mensen, houd van mensen, houd van of contact, contact brengen, niet alleen voor mijzelf, maar andere mensen ook in contact brengen. Weet je, de eerste behoefte van mensen eigenlijk contact met mensen en met jouzelf. In Nederland is dat heel minder zeg maar, vergelijk met Ethiopië, hier is individual mensen, tuurlijk in Ethiopië was misschien iets anders. De tijd, het is anders, modernistisch of globalisation of [onverstaanbaar], maar weet je, je leert van mensen en je hoort bij mensen. En je hebt het nodig andere mensen, die heb jou nodig, maakt niet uit wie jij bent en waar, welke niveau waar jij zit.

[i] Je gebruikt je identiteit als ik het goed begrijp gebruik jij je identiteit als vrouw uit Ethiopië om hier contact te maken met anderen?

[r] Toen begin, ja tuurlijk, mijn, mij, ik gebruik puur om mijn identity, maar als ik nu terug zie, ik weet niet als identity, iets iets het is anders, weet je, dan de andere, dus laten zien. Het is niet dat dat de strong identity uit Ethiopia, het wordt steeds minder, het meer jij, jij bent hier, je voelt hier thuis, je, je bent hier dagelijks. Maar ook die kan jij niet loslaten wat je had, want die helft, ik kwam toen ik 26 dus, half mijn leven is, daar heb ik niet, ik, ik ben daar geboren, opgegroeid. Dat kan ik niet loslaten. Maar ik, ik pas aan mijzelf ook hier, vaak.

[i] Dat is heel mooi wat je zegt, hoe op basis waarvan maak jij dan keuzes hier in Nederland? De keuzes bijvoorbeeld om te kiezen voor vrijwilligerswerk te doen en voor het theater en voor. te werken in Den Haag, Utrecht, in Leidschendam, in Rotterdam. Je bent zo actief. Wat, ja hoe komen die keuzes tot stand?

[r] Soms kies bewust, soms onbewust, soms moet ik kiezen, omdat ik heb geen andere opties. Dat, dat is de pijnlijk.

[i] Ja?

[r] Alle vrijwilligerswerk toen gedaan in begin. Toen begin was voor mij was belangrijk om contact brengen, ervaring te doen. Later voor andere mensen, eigenlijk, ik wil niet dat de tijd zo, zo moeilijk wordt voor anderen net als ik, ik heb dit weg nu gezien. Waarom zou ik niet voor andere mensen die weg laten zien, waarom hij moet zo lang wandelen die weg te vinden?dat is mijn motto, ik weet hoe moeilijk is, dus ik wil voor anderen makkelijker maken de weg, dat is 1. En ten tweede is dat vrijwilligerswerk. voor mij is of een manier om ervaring te doen later ook omdat ik heb niet rechte beroep gemaakt, dit is mijn beroep, die heb ik de opleiding gedaan. Dus kan ik niet in 1 richting gewoon bepaald carrière maken. zoals wat je hebt gezien, mijn leven was gewoon ja, heel anders gelopen dan wat ik wil, hoe wil ik. Dus ik moet weg vinden, die bij mij, voor mij iets wordt. Dus. hopen dat elk elke opportunity, ik pak gewoon. Elke kans, klein, moeilijk, of makkelijk. voor mij is beter dan niks, dus daarom ik overal ben ik ja betrokkener eigenlijk, ik wil niet maatschappelijk werkster, als professional kan ik niet werken. Maar door vrijwilligerswerk heb ik dat, dat behoeft.

[i] Ja.

[r] Dat hoe heet nou in Nederland, ik krijg van, hoe heet nou, verdiening, hoe heet je in Nederland, krijg ik satisfaction, hoe heet?

[i] Satisfaction.

[r] Dus dat is 1. Voldoening?

[i] Ja, voldoening.

[r] Voldoening dat ik kan ik niet als professional met carrière kan niet bereiken, maar door de vrijwilligerswerk je kan, ik meer, dat dat te doen. En de tweede is, zoals wil ik zelfstandig zijn, ik moet alles proberen. Ik ik ik moet het, het is zo vermoeiend dat elke keer met de te kiezen. Elke keer, ik ik kies niet de makkelijkste weg. omdat de makkelijskte weg bestaat niet voor mij, of ik ben zo ambitieus, dan past niet bij mij om passief te zijn. Maar is ook, ik heb verplicht ook, ik moet werken, maar dat werk, maar krijg dat werk. die mij mij mijn niveau is, het is een hoger mentality, maar in mijn maatschappelijk niveau er zitten lagen, die botsen.

[i] Ja.

[r] Dus is zo vreselijk.

[i] Zo tegenstrijdig.

[r] Ja tegenstrijdig. Die mijn ambition, mijn droom, mijn verlang, mijn wens, zo hoger. En de realiteit, ik zit gewoon in lagen, in lager niveau qua voor mijn leven. Dat is heel, heel pijnlijk te accepteren. Ik zou niet ook dat gewoon zo blijven, ik wil zo mogelijk verwerken en ook een moment vinden dat ik uiteindelijk dat, hier gewoon iets vast, gewoon iets, gewoon thuis voelen.

[i] Maar, voel je je hier niet thuis dan in Nederland? ik bedoel, ik voel wel thuis, maar zijn de dingen die ik mis.Je hebt. Weet je, je hebt zekerheid, je hebt zelfstandigheid, je hebt de vrijheid. Dat dat is de belangrijkste in mij, maar soms heb ik moment dat dat had ik niet, dan voel ik mij niet thuis, dat ik ik word dwingen bijvoorbeeld, omdat ik uitkering krijg, dingen die niet willen werken. Of, ik word ergens verplaatst, tussen de mensen, ik heb wel alle respect van elke mensen, maar die mensen nooit gewerkt heeft, niet over cv nooit gehoord, dan krijg ik voorlichting, ja jij moest jouw taakvoorstel, elke ochtend doen. Ja dat is zo bij dat bepaalde traject zit jij in traject mensen die langer niet gewerkt, maar je moet tussen die mensen zijn, want jij krijgt uitkering. Op dat moment weet je, ik wil weg, want ik ik ik. ik hoorde niet daar, mijzelf, met alle respect. ik verdien wel andere position, uitdaging. Op dat moment weet je, dan voel ik, ja, zoveel pijn. en zoveel onzekerheid, zoveel onmacht. ik weet niet waar ik wil weg, maar ik wil van dat soort weg, dat vluchten gevoel, dan voel jij je niet thuis. Dat is het.

[i] En hoe pak je dan jezelf weer op en zeg je van oké? Nieuwe dag.

[r] Nieuw begin.

[i] Nieuw begin, nieuwe uitdagingen, hoe, hoe doe je dat?

[r] Ja, ik ben 3 keer in uitkeringinstantie, mijn uitkering was gestopt, omdat ik, ja. Maar gelukkig, ik pakt mijzelf terug, omdat ik, ik kijk heel ander, mijzelf, omdat ik ik ik wil nu dit, dat dat als de ander wil. zij willen niet voor mij, dat is regel dit niet, voor dit ik kan jou voorbeeld vertellen. Toen ik bij GGD Utrecht werkt, ja het is tijdelijk project voorlichting, mooi je werkt met ambtenaars. En stop, na 3 maanden moet ik weer in uitkering gaan zitten. Tuurlijk dat is ik heb een brief, integratie, ja toen ben ik gewoon, ben ik naar die afspraak. Ik dacht weet je ik krijg intake gesprek, wat heb je gedaan, wat wil je graag doen of zo, maar ik word gelijk van plaats, ja je moet je schoenen uit, die nieuwe schoenen. Dan moet jij daar in dat productiewerk. 100 mensen in ander, in kamer, gewoon dan eerst moet uitleggen, je moet hallo dan zeggen mensen, je moet jouw tanden elke ochtend borstelen, je moet netjes zijn. En ook de ergste was, de ruimte voor mijn ogen is heel heel niet geschikt, chemische dingen bij elkaar, het was gevoelig. Toen, ja, toen heb ik daar 3 maanden gewerkt, maar ik ben bijna burn-out. Van al al stof, alle dingen. Toen was ik verplaatst naar ook groen, groen werk heet. Dat was ook chemisch binnen, de kast was niet goed. Ik ben bijna van benauwd, mijn ogen kan niet slapen. Oké, in dat proces ben ik een jaar gemaakt, weer heb ik het werk en daarna ook word werkloos. Ben ik ook dwingend [gedwongen] bij kringloopwinkel geplaatst. Ik heb alle respect, maar het probleem, mijn ogen is heel gevoelig voor stof. Ik moet in in schone omgeving te zijn. Oké, op dat moment wat voel jij? Als ik nee zegt dan heb ik geen huis, ik word dakloos, mijn uitkering wordt stopt. Wat ga jij zeggen? Ik heb toch eigenlijk de medische redenen. Eindelijk duurt zo lang, maar intussen was ik aan het solliciteren bijvoorbeeld. Gewoon ergens. Dan krijg ik baan of ik heb een ander vrijwilligerswerk. in een wijk voorbeeld, bij de wijkcentrum. En zij vroeg mij ook omdat ik uitkering krijg, mensen hebben een gevoel dat je bent niet motiveert of je bent niet, wat ga je voor ons doen? Ik zeg wat hebben jullie voor mij hier, ik kan alles. Nee vertel wat jij wil bij ons, bij ons. Ik zeg geef mij een kans, ik kijk hier wat de activiteit hier. Tussen die tijd ze hebben mij laten, 200 borden laten wassen met mijn hand, en ook, ik moet 1000 flyers in de wijk door brengen, omdat van een uitkeringsinstantie hebt een negatieve report. Mevrouw zij wil niet in de kringloopwinkel werken. Dus je hebt gewoon, je bent in de blacklist, terwijl het is niet gezien zoals jou. Na een week heb ik plan schrijven wat ik wil doen in de wijkcentrum. Toen ik heb gezien heel weinig buitenlanders vooral daar komen. Ik, ik weet het niet de omgeving, maar komen wel hier buitenlanders, vraag ik. Ja, maar ze kom niet bij ons wijkcentrum. Oké ik wil het proberen die mensen hier krijgen. Nou doe maar. Toen ik heb een bijeenkomst elke week georganiseerd. Begon vrouwen, ik, ik ga bij op school, op straat, op supermarket, die vrouw in gesprek. Toen organiseert 1 keer per week voorlichting geven. Dan zij gelooft pas, maar dat gelegenheid krijgen is niet zo maar ook. Toen kwam mijn contactpersoon na een week, zij was op vakantie, zij moet stemming geven voor dat mag ik daar werken, want ik heb in de kringloopwinkel.. Tijdens een gesprek aan de tafel. Ik weet het niet hoor, met die mevrouw wie werkt, ze is heel echt, ja, ik weet niet welke werkgever voor jou werk heeft. Tijdens de gesprek. Later, die, die mevrouw die mij ook, weet je, die voor mij baas zou zijn, ze hebben indruk, negatieve indruk over mij. Daarom ze heeft naast die bord laten wassen, bezorgen. Dat betekent, je kan niet zelf zijn, weet je dat soort frustratie. Je wordt niet gekijken als mens, je bent zo. Dus, uiteindelijk, zes maanden heb ik in dat wijkcentrum, ik heb mooie aanbevelingsbrief gekregen. Zij zeggen zelf 200 procent zij hebt gefunctioneerd. En toen later zij is naar, bij de, van de contactpersoon die hebt mij over mijn negatief die brief gestuurd, ja mevrouw zo, zo, zo.. Weet je, dan moet je bewijzen, bewijzen is zo moeilijk. Je moet je tien keer bewijzen om echt jij als goed persoon zijn. Dat bewijzen is vermoeiend, soms je kan niet bewijzen want je krijgt niet de kans ergens jou laten bewijzen.

[i] Dat, ik kan me voorstellen dat het oneerlijk is.

[r] Ja, geeft dat, geeft onzekerheid dat geeft frustratie. Dat geeft jou ook weer als vluchtelingen, je kan zeggen, oh als het mijn land was. Het is niet waar, maar toch weer geeft jou heel veel gevoelens, boven te komen, je bent nog vlucht. Jij steeds jij wil graag weg, maar je weet niet waar heen weg. Dus dat is het wat dit soort dingen geeft jou eigenlijk heel onrustig. En dan, dat, dat niet jou, ja.

[i] En toch denk ik nu aan wat je vertelde over Utrecht, dat je daar bent en dat je een bepaald soort rust ervaart.

[r] Ja, opnieuw beginnen voor mij is, tuurlijk het is spannend, uitdaging, maar ten minste dat ik de ruimte krijg hoe dingen wil ik doen. Of dat mijn talent kan ik gebruiken en mijn talent benutten. Kan ik ook ontwikkelen als ik in tussen. met jou, met mijn collega die, weet je, ik kan leren. Misschien ook zij kan van mij leren, dat kan ik ook misschien bijdragen, die talent wat ik heb en misschien anders. Mijn werkgever, de ex-werkgever in Utrecht, tijdens de afscheid, afscheid van mij, ik bedoel de project is klaar, hij zegt, ze waren drie mensen voor die vak geselect, gesolliciteerd. De twee mensen is heel echt prima, goed Nederlands spreken, schrijven. Maar ik heb wel de ander gekozen, dat was [naam] hij zegt, zij was ambitieus. Ik weet zeker zij houdt het wel, zij wil dat werk doen. Ik zei laat maar over die Nederland, ik ga het schrijven dat kan ik het compenseren met haar.. Nu, ik heb helemaal nooit spijt gehad dat ik heb haar gekozen, zij zegt. Dus sommige mensen wel zij kijk hoe als persoon jij zijn. Sommige mensen door de taal, weet je ze hebben andere beoordeling. Toch wel als een persoon dat jij. vindt dat je hebt, die jou accepteert, of je probeert jouw, wel, jouw kwaliteiten te gebruiken, niet alleen maar de negatief of de mindere kanten zien. Iedereen heeft zwak punten, voor mij de taal is zwak punten. Ook in andere dingen misschien.

[i] Maar goed jij, je bent je wel bewust daarvan en ik ik, je gaat daar ook op een bewuste manier mee om en ook dat is toch een heel groot talent van jou ook, denk ik. ja ik, ik zou mooi zijn als ik nog goed beter naar Nederlands spreken. Nu ook, ik ben bezig met Nederlandse taal. Maar, ik denk niet dat is dat zou echt echte belemmering handicap zijn om niets te doen. Want als die werk wat ik heb gedaan. sowieso, heb ik gedaan. Misschien wel voor mijn collega lastig zijn, maar toch wel met andere dingen ga je compenseren. Ik adviseren ook iedereen ook, doe maar wat bij jou, niet denken alleen maar ik kan niet goed Nederlands spreken.

[i] Vind je dat, ja, hoe, je ervaringen in Nederland, denk je dat vluchtelingen gelijke kansen krijgen als anderen? Ik denk niet, niet alleen de kans, maar is ook vluchtelingen is heel ander soort, ander soort mens. Als jij nou vraagt migranten, hier bijvoorbeeld zijn Surinamer, Marokkaans gast gastarbeiders gekomen. ik kan niet ervaren de eerste generatie, maar daarna. Zij heb familie hier, dus de omgeving helpt jou, om dat kans te krijgen. Je hebt oma, je hebt tante, misschien die kennen ook bedrijven, die netwerk helpt jou. Maar vluchtelingen heeft dat niet. Vaak is of alleen gevlucht, of vaak een ander trauma ervaring heeft, dat verwerking duurt. Ook de procedure van asiel ook is niet zo makkelijk, het is niet, het is nog gewoon klaar kant, je moet door gaan met als die procedures. Je wil iets, je wil iets doen? Je wil iets werken, je wil iets leren, maar je mag niet! Dat betekent omdat jij vluchteling bent. NHB bepaalt, ja bepaalt obstakels, dat maakt het, zij krijgt minder kans, maar de situatie is. wel speelt een grote rol. ja dat dat heel jammer, zo veel potentiële mensen. Door al die procedures, ook in mijn werk, ik heb gewerkt mensen die eerder papieren krijg, die de kans krijgen, opleiding doen. Meer, meer zij zijn geluk in hun leven en ook makkelijk in de Nederlandse samenleving. Ook hier thuis voelen. De mensen niet op tijd krijg kans krijg, die zijn isoleerd, qua taal ook. Qua van alle ervaring. Dus ik denk het is bij vluchtelingen, het is niet gelijke kans.

[i] En jij hebt de Nederlandse nationaliteit?

[r] Ja.

[i] En waarom heb je daarvoor gekozen? Uiteindelijk? En wanneer, wanneer kreeg je de Nederlandse nationaliteit?

[r] Ik heb 2001 Nederlandse nationaliteit aanvraag gedaan, aangezien dat. Ik zou niet naar Ethiopia toe gaan, ik zou niet , op dat moment voor mij is niet, is niet veilig. Sowieso ik ik mag niet ook twee nationaliteiten houden, dus ik heb gekozen voor Nederlandse nationaliteit. Het is wel echt gewoon dubbel gevoel, dat je, nu nu nu nu is het veel minder, maar toen was, ja het is een dubbel gevoel. Weet je als of jij, jij. je had niks, weet je, je had de landen niet, je had je ouders niet, dat nationality gevoel ook dan erbij ook weet je, ja, doorgeven, loslaten. Dan dan voel jij weet je dankbaar, maar het blijft altijd meer als jij bent hier meer, nu ik zou niet anders, zeg maar. Maar wel mijn ouders vinden het moeilijk, mijn vader vooral. Ik heb niet stemming gevraagd, maar wel ik heb doorgegeven. Hij vindt het zo erg, dat ik, dat ik heb andere nationaliteit. Ik heb dat meegenomen, dat ben ik niet meer Ethiopisch. Maar ook qua van andere dingen, ja, bedoel ik. Ik weet het niet, geeft verwarring. Soms weet je, oh ik ben niet Nederlander of ik ben niet Ethiopisch, bepaalde moment voel jij je niet ergens. Je bent in Nederland met nationaliteit, maar zoals vorige keer heb ik jou gezegd, weet je, meer in de probleem zit. En je weet het niet waar, je voel mij niet ergens waar je hoort er bij.

[i] Voel je je ontheemd? Voel je je ontheemd?

[r] Wat is ontheemd?

[i] Ontheemd is dat je eigenlijk geen land hebt. Nergens.

[r] Nergens.

[i] Bij geen enkel land hoort.

[r] Zoals ik heb jou gezegd, ja bepaalde moment voorbeeld, ik heb probleem met met een sollicitatie, zo niet, met mijn uitkering. dat of dwingend wordt, op dat moment ja vaak komt terug dit. Ik ik dacht ja ik ga weg, maar ook in Ethiopia, daar hoort ik niet bij ook. En hier ook zo! Dus. Omdat het van vluchtelingengevoel misschien de andere mensen ook Nederlanders, zij zou nooit dat zo voelen, maar ik, ik hoor nergens bij. Er is wel, komt terug vaak, vooral. als ik geen kans krijg, of als ik, ik werkloos zijn, weet je de de grootste probleem voor mij dat, ik houd van gewoon iets iets te doen. Nu zeg, het moment daar heb jij dan niet ergens vasthoudt. Voor voor die zelfstandigheid, ik heb alles sacrified, van alles. I don’t have family here, ik heb geen carrière, weet je ik ik heb, de ene ding wil ik ten minste zelfstandig zijn.

[i] Dat klopt, dat ervaar jij zo en als je nu de vraag omdraait, van wat heb je wel hier?

[r] Wat heb ik wel hier? Misschien als je bij de Nederlanden niet bent, misschien ik zou niet zo misschien wijs zijn, dingen, omdat zoveel, zo veel ervaringen heeft, de up en de down. maar niet alleen up en de downs, maar ik heb ook goede momenten, voorbeeld die Kartini-prijs. Dus, en en gevoel krijg, oké, dan ik ben iemand van iemand anders. Ik ik word gekijken bij iemand anders dan ik in mijn spiegel kijk. Dat dan dan dan dan jij, ja soms ook andere mensen zeggen zij zeggen te weinig, ook hoe jij. weet je, sterke vrouw, hoe doen ze daar bij, hoe doe jij dat eigenlijk, waar krijg je de energie, dan dan beetje stil staan, ja dan dan, dan kom ik terug, oké, ik weet dat ik word [of werk] hard. Ik werk hard, maar qua van weet je, concreet iets, dan het moment dan heb ik heel veel te doen, maar zo weinig bereikt, ik bedoel persoonlijk succes. Als ik beschrijf mijzelf dan is het met werk, een stapje omdat te troe.., tegenslaan maakt soms, dat is onduidelijk. Maar denk ik nu, ik ben in goede weg. Op dit moment, ja, ik werk ten minste. En ik doe ook nu al die talenten tot nu wat heb ik gedaan of vrijwilligerswerk of cursus, of workshops, whatever it is. Wil ik graag dat in als ik niet loopbaan, loopbaan, maar ten minste ga ik als freelance, dit wil ik doen.

[i] Want je doet eigenlijk heel veel leuke dingen, je doet heel veel nuttige dingen ook, voor, voorlichting geven. dus je speelt nu in het Wijktheater eigenlijk werk jij wel, ik begrijp dat je graag zou willen dat een instantie dat zou erkennen? Maar is dat echt..

[r] Zelfstandig zijn, niet alleen de erkennen, maar dat aan mijn brood komt. Uiteindelijk ik zelfstandig, dat, dat zelfstandigheid, dat economie ik zelfstandig ben.

[i] Economisch zelfstandig zijn, dat zou jou, in de toekomst is dat een droom voor jou?

[r] Ja, ja, dat geeft jou vrijheid.

[i] Ja.

[r] Zoals jou vertelt, als jij vrijheid jij bent gezond, gelukkig. Je bent eigen, eigen, eigen zelf, je bent niet van iemand, weet je, je bent met jezelf.

[i] [Naam] ik had ook gelezen dat je van Delfts Blauw houdt?

[r] Ja, het is waar. Ja, ik ik de ene ding dat tuurlijk, in Nederland, als ik, als ik kijk, vraag, Nederland is ook mijn land geworden. Ik houd ook van de Ethiopische dingen, maar van Nederland, Delfts Blauw, niet alleen Delfts Blauw, maar ook royal familie, ik weet niet dat dat geeft mij, weet je, daar ben ik. onbewust, onbewust misschien bezig, dat geeft mij goed gevoel. Dat alsof weet je, gewoon iets vasthouden.

[i] Had je een keer ook koningin Maxima ontmoet?

[r] Klopt.

[i] Hoe was dat?

[r] Voor mij? Ja, het is, het was zo na cursus voor onderneming van vrouwen, en ik ik er was veel vrouwen die hadden die cursus gedaan en bij de certificaat uitreiking, er is iemand, er is een boekpresentatie boek, hoe wordt. wordt, moet doorgeven voor Maxima. Toen de organisatie [naam] jij moest geven voor Maxima. Weet je, de ander mijn cursus allemaal, vaak zij zijn Nederlanders, zij hebben eigen bedrijf of ze is gewoon. ik ben de ene vluchteling die zit in dat opleiding, ik ben de ene die goed Nederland spreekt, niet goed Nederlanden spreekt, en juist is zo, ja, toen zij zeggen het wel, maar achteraf, ik heb gehoord. omdat jij bent zo doorzetter bent, die opleiding heb jij bijdrage betaald. Er is niemand van vluchtelingen of Afrikaanse achtergrond of nieuwkomer, zelfs durven niet opleiding te komen, dat voor voor voor ons. voor jou is extra promotion, zij zegt later af. Dan heb ik dat boekje ja doorgegeven voor de prinses Maxima. Zij is fijn, eigenlijk met haar ja spreken, maar is even kort. Maar nu nu gebruik echt als een promotion materiaal soms, het geeft wel iets.

[i] Heb jij nog iets wat je zou willen vertellen over jou bijdrage aan bijvoorbeeld Utrecht? Als stad, als plek waar jij komt en werkt?

[r] Klopt. In, kijk, in Den Haag heb ik de Kartini-prijs, maar ik heb ook gemeentelijke onderscheiding. gemeente Den Haag, 10 jaar relevant werk, 2012 het moment, vanaf het moment ben ik 1 dag in Den Haag, ik was altijd bezig geweest. Oké, Leidschendam ook een theaterproject. Nu is de volgende stap denk ik de meeste contacten nu heb ik in Utrecht. Toevallig mijn oude baan, heb ik vaak daar opleiding gedaan. Nu ook, voor BMP, Ongekend Bijzonder. Ik ben 1 of de 4 werkers van de Ethiopische gemeenschap in Utrecht. Eigenlijk ik heb dit ja dit baan gekozen, juist, het gaat over vluchtelingen en bijdrage in Nederland. Als vluchtelingen ten eerste zelf een steentje bijdragen en ten tweede dat Ethiopische mensen in Utrecht zichtbaar maken. Ik heb het wel gezien van de vorige week hoe moeilijk is dat te bereiken. Maar ook zichtbaar maken, maar ook in het groepstraject. ook in hun proces te helpen, ook een weg, ten minste te participeren, in een persoonlijk levensverhaal. Tuurlijk. Het is vooral de contact naar wat ik zoek tijdens werving. Soms, echt wel het het heel zwaar werk, maar toch soms als in 1 keer dan mensen gevonden, interview. Ik word ook inspireerd door de verhalen van de mensen. Ik leer hier van, van hen daar. Ik, ik waardeer ook welke manier is, weet je, het leven hier opbouwt, of te zien. En later ook die werk, als ik het in een museum, in archives, in de bibliotheek komt. Dit is mijn oude baan, oude vak. Weet je, in andere manier, wel ik ben bezig wel iets, ja iets in bibliotheek of archief, museum iets te zetten. Dat geeft mij ook weer gewoon een voldoening. Dus, dat doe ik graag. Goed, ik heb, ik heb het, volgens mij, ik heb het echt heel veel verteld. De ene ding wat ik wil zeggen is, vluchteling, zij verdienen een kans. Van welke reden is, verlaten eigen land, dat is de moeilijkste beslissing in leven, of wonen in ander land. Zelfde is gewoon als graag morgen voor jou, ga maar naar Amerika. Gewoon zonder iets, worden allemaal geregeld. Zou moeilijk zijn, ja achterlaten jouw kennissen, jouw collega’s, de culture, de omgeving, toch dat zelf en moeilijk. Dus, en vluchteling heeft dat. Vaak is verdwingen [gedwongen], zonder wil dat moet hen van dat land verlaten. Maar als zij komt in nieuw land, ook, ja, kansen krijgen, gewoon. En ook laten zien aan hen talenten ook, of talenten gebruiken.. Vooral het is zonde die hoger opleiden mensen, gewoon het is, zou potential [mogelijkheid] zijn voor Nederland. Of een andere mensen van andere land te brengen hier te werken en opleiding te geven. Beste Nederland is een of de landen die scholarshippen geeft voor andere landen, voor dezelfde [onverstaanbaar]. Terwijl wij vluchtelingen, wij willen graag leren, maar heel weinig mogelijkheden. Dat is, dat vind ik heel jammer en ook zou beter zijn dat de kans krijgen. En bedankt.

[i] You chose an object? And would you like to tell me why you chose this object?

[r] I chose it when I look back, what have I done in my life. It gives me an answer.

[i] An answer?

[r] In Holland, yes.

[i] An answer to what?

[r] Answer what, what have I accomplished in my life, especially in the Netherlands. From career, or family, or so to speak, work, then I really have very little, to get the answer, but this is a recognition. What don’t I know or don’t expect, things that I just, because it has to be done. But, but, but there is someone who sees that work is important was. And has contribution to society. Then I think to myself, okay, I have achieved.

[i] Because, you know, it’s a prize? And what’s the price for and what’s it called?

[r] The prize is called Kartini Prize, it’s someone’s annual emancipation prize from The Hague. It is awarded on International Women’s Day. But it is not just an award, the jury selects 3 for it. for the layer people, it can also be a product, it can also be a person, it can also be a company, it can also be a foundation. In my case I was nominated. as a person [name], what has to do with emancipation of women and men in The Hague has a contribution, so emancipation prize from the city of The Hague is contribution of. equal, equality of women and men. In my time 32 were nominated. There, then 3. chosen. There was also a public prize via internet as well, people have to vote, but the jury is also paid that prize, so coincidence I won both. The public prize too, the Kartini Prize. Among other things, why did I get that, it says in the jury report that I have made taboo subject discussable, within African Ethiopian community, such as fgm, domestic violence. To be a role model as well, to simply participate in Dutch society. I organise intercultural activities from Ethiopian culture to the Netherlands, among other things, I show to the Dutch and vice versa. from Ethiopian or African to Dutch culture, so it is intercultural activity among other things. But is also a role model of Dutch refugee women in The Hague.

[i] Can you introduce yourself?

[r] My name is [name]. I am 46 years old. Yes, I live in Leidschendam. I am 20 years in the Netherlands. 1994 I came from Ethiopia to the Netherlands as a refugee. Now I live in Leidschendam, before that it was in The Hague, and at the moment I work in Utrecht, that is.

[i] Hey and in Ethiopia, can you, can you tell something about Ethiopia, where you lived and also about your family?

[r] Yes, I was born in northwest Ethiopia. With a family of five. Two girls and three brothers and I had a normal childhood. I had high school, elementary school, then high school in the city. And then in the capital I studied university, librarian, then in my time was actually a 2 year, then degree and then I worked.

[i] Did you work in the library in Ethiopia?

[r] Right. I worked in the library and the librarian profession is so different from the library. Public Library or Ministry or University, I worked in special library, special library is certain subject for engineers, more technical books, yes, then I was a librarian. Then yes I don’t want to go further in field of librarian, because I would like to work more people. Then at that time start also librarian is more. yes computer, computerized and therefore, training in yes librarian was just another, different steps to go, information service, but I did not choose that. I was studying sociology that time. Because I like people, culture and that’s why I think I work more with people. In between I came to the Netherlands, I didn’t graduate from sociology. And yes, turns out now that I’ve ended up with a very different career, that’s a pity actually, I didn’t do much with my sociology studies. Yes, that wasn’t the time, I mean I was in the asylum seekers’ centre. I had to wait 6 years and I turned 32 and so I couldn’t ask for study funding, I couldn’t go on studying. And at that moment I don’t know, I didn’t know UAF what. I was in Zeeland, really in the village.

[i] Because you’re from Addis Ababa?

[r] Yes, originally me, my parents, I was born in Northwest, but I also lived, worked, yes, in Addis Ababa.

[i] And before you come to Holland, do you live in Addis Ababa?

[r] Yes.

[i] And then you come to Holland?

[r] Yes, then I come to Holland, yes.

[i] And around what year is that?

[r] That was 1994. That’s December. It was 24, I’ll never forget it was Christmas actually in Holland, so I have to wait three days in the application center to get in, because there were yes Christmas.

[i] Hey, and you arrive in Holland and where in Holland?

r] First I was in shelter, called OC, shelter temporarily in Gilze and Rijen. That is in Brabant and I stayed there for three months, yes after three months as everyone had to go to asylum, called AZC, that is longer, longer stay waiting. bleaching, I had moved to Goes, Zeeland and then also, yes Goes was closed and I am still in Burgh-Haamstede, that is also in Zeeland, is a small village. There I waited for the last term asylum seekers procedure.

[i] And how were you, how were the first impressions in the Netherlands for you, do you remember what happened, what did you experience then?

Right. One or the things, is that was for me was that a shock, yes, I, it was in December, I do not have the right clothes anyway, but still if I have seen trees outside without leaves, while is wet and freezing. In Ethiopia, it is, you can only trees without leaves when dry, that was that, a controversial [controversial] for me, still day and night is also, it goes dark early. It doesn’t get sunny in the morning, that’s a big confusion for me, shock. Really the cold. But also the positive impression how the streets were so neat and so many cars, but you see as if, you know, just walking like that, like that, like that, that was my first impression, was in the Netherlands.

[i] And how did you feel then?